Strabismus

This is a condition in which both eyes do not look at the same place at the same time. It occurs when an eye turns in, out, up or down and is usually caused by poor eye muscle control or a high amount of farsightedness.

This is a condition in which both eyes do not look at the same place at the same time. It occurs when an eye turns in, out, up or down and is usually caused by poor eye muscle control or a high amount of farsightedness.

There are six muscles attached to each eye that control how it moves. The muscles receive signals from the brain that direct their movements. Normally, the eyes work together so they both point at the same place. When problems develop with eye movement control, an eye may turn in, out, up or down. The eye turning may be evident all the time or may appear only at certain times such as when the person is tired, ill, or has done a lot of reading or close work. In some cases, the same eye may turn each time, while in other cases, the eyes may alternate turning.

Strabismus usually develops in infants and young children, most often by age 3, but older children and adults can also develop the condition. There is a common misconception that a child with strabismus will outgrow the condition. However, strabismus may get worse without treatment. Any child older than four months whose eyes do not appear to be straight all the time should be examined.

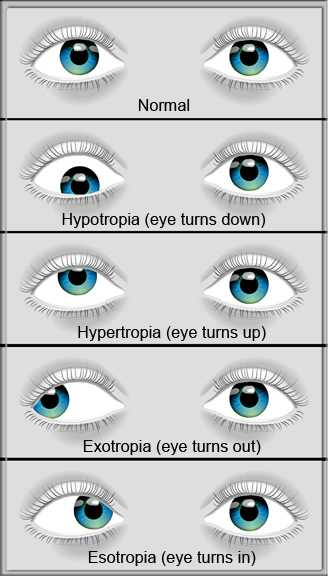

Strabismus is classified by the direction the eye turns:

- Inward turning is called esotropia

- Outward turning is called exotropia

- Upward turning is called hypertropia

- Downward turning is called hypotropia

Other classifications of strabismus include:

- The frequency with which it occurs – either constant or intermittent

- Whether it always involves the same eye – unilateral

- If the turning eye is sometimes the right eye and other times the left eye – alternating

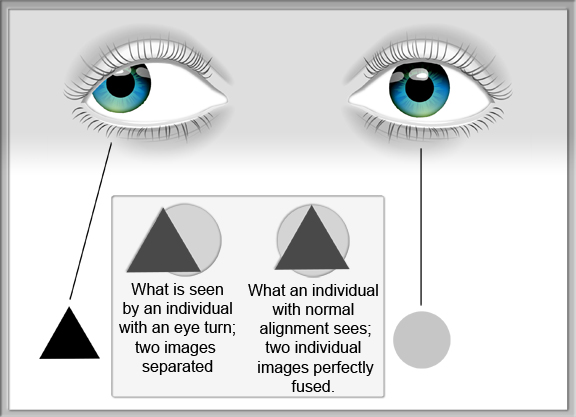

Maintaining proper eye alignment is important to avoid seeing double, for good depth perception, and to prevent the development of poor vision in the turned eye. When the eyes are misaligned, the brain receives two different images. At first, this may create double vision and confusion, but over time the brain will learn to ignore the image from the turned eye (suppression). If the eye turning becomes constant and is not treated, it can lead to a condition called amblyopia or lazy eye.

Amblyopia

Also called lazy eye, amblyopia is decreased vision that results from abnormal visual development in infancy and early childhood.

Amblyopia develops when nerve pathways between the brain and the eye aren’t properly stimulated. As a result, the brain favors one eye, usually due to poor vision in the other eye. Normally, the images sent by each eye to the brain are identical. When they differ too much, the brain learns to ignore the poor image sent by one eye and “sees” only with the good eye. The weaker eye tends to wander giving it the label “lazy”. Vision in the amblyopic eye may continue to decrease if left untreated and vision loss can range from mild to severe. Over time the brain simply pays less and less attention to the images sent by that eye. Eventually, the condition stabilizes and the eye becomes virtually unused.

The goal when treating amblyopia is to maximize clarity of sight (visual acuity), to normalize the tracking and focusing skills of the amblyopic eye, and thus to teach the brain to use both eyes together. Once good binocular vision is achieved, the chances of maintaining long term improvements are high.

Signs and symptoms of amblyopia include:

- An eye that wanders inward or outward

- Eyes that may not appear to work together

- Poor depth perception

A person may also exhibit noticeable favoring of one eye and may have a tendency to bump into objects on one side.

Although amblyopia usually affects just one eye, it’s possible for both eyes to be affected. Sometimes this condition is not evident without an eye exam. If you notice your child’s eye wandering at any time beyond the first few weeks of life, consult your child’s doctor. Depending on the circumstances, your doctor may refer your child to a specialist in eye conditions. It is reccomended all children have a complete eye exam between ages of 3 and 5. There is a long standing misconception that amblyopia cannot be treated beyond a certain age however, numerous recent studies have shown that this is not true.